A 2008 Gartner study on social software noted that “about 70 percent of the community typically fails to coalesce.” While the measurement and the statistics behind this statement raise questions, there is an element of truth….

There are detrimental effects of over-hyping the technology and then committing the three cardinal sins of running a community:

- If you build it they will come. This is probably the best known online community fallacy. The premise is that if I roll out a given technology set (blogs, forums, wikis, etc.), users will automatically appear and congregate, forming a robust community. This can be attributed to the lure of “social software” that companies repeatedly bite at, as opposed to seeking to extend or create value for their customers.

- Once I’ve launched it, I’m done. Many communities launch successfully, only to fade out and disappear. This is due in large part to a failure to assign ownership of the community and to have a strategy that lasts past “launch.”

- Bigger is better. The assumption here is that the overall size of a community is indicative of its success. This is challenging for most community managers and businesses to understand, as it is contrary to what they’ve usually been told.

All three can cause a community to fail, and there are plenty of examples. Understanding the community life cycle can help you avoid making these mistakes.

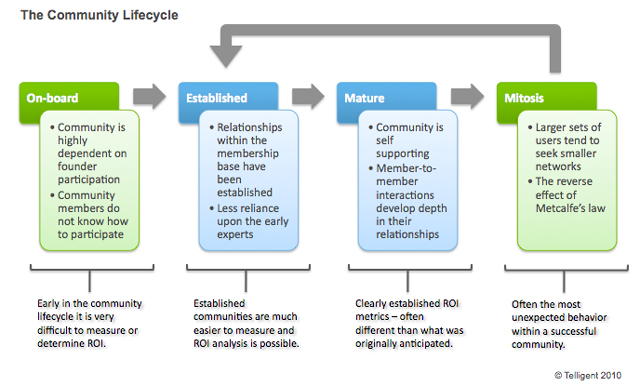

The image below is representative of the different stages of the community life cycle. It’s important to recognize that this is a macro-view, and that within and between the stages are smaller life cycles (learning, innovation, etc.).

A community is constantly in one or more of the following states with the exception of the On-Board state:

- On-Board: This is the starting point of any community, characterized by people (seekers) looking for value (content), most of which is created by the community’s founders.

- Established: The community is becoming self-sustaining, with the members (influencers, originators, etc.) creating and maintaining value within the community, although some reliance on the founders is still necessary. It is the established phases of the community where analytics can be used to understand user behavior and value.

- Mature: The community is self-sustaining, and clear relationships between individuals are being formed. Users are organized into clear types (influencers, seekers, moderators, originators, etc.) and take full ownership and responsibility for content. Little to no supervision is required by the founders, who become no more than credible participants.

- Mitosis: Core community members become disenfranchised with new participants who don’t share the same values. These core community members seek more focus as they gravitate towards specific topics and relationships. Successful communities enable this and allow the community to split into smaller nodes, thus returning to an Established phase and repeating the life cycle process.

Most discussions surrounding the topic of community life cycle are based on the work done by Bruce Tuckman’s stages of group development: Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing.In addition, much of the value proposition for “bigger is better” is based on Metcalfe’s law, which states that the value of the network increases as the number of connections within the network increases. Hence the common belief is that the size of the community is a clear indicator of the value of the community.

It is important to note that Metcalfe’s law was created to describe telephone and facsimile networks. What’s not often considered is that social networks are dependent upon people, and people cannot obtain the same value from network size due to the “cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships,” otherwise known as Dunbar’s number. While Dunbar never proposed a specific number of relationships, most researchers agree that it is approximately 150.

Community life cycles are often portrayed as simple linear progressions, with the goal of “maintenance” once maturity is reached. However, I have found that a community has unique characteristics that conflict with many of the preconceived notions of success. While the value of the community to its creators increases as membership increases, the value to individual members may diminish. Disregard for, or lack of understanding of these behaviors can lead to the failure of a community.

A great case study here is Twitter. There are some people who believe that Twitter provides value through the size of their network and number of their relationships. Examples would include politicians, media, actors, and so on. They don’t maintain relationships individually, but with an audience of followers. However, there are people who find Twitter’s value diminishes as the number of relationships they manage increases, as the initial draw was the ability to manage relationships, not an audience.

It should be noted that I am not advocating that communities be limited by membership size. Rather, capabilities should exist within a larger community to support smaller, internal groups that can form around narrow areas of interest. This is validated by both Twitter and Facebook, which have in recent months both introduced capabilities to narrow the scope of conversations: Lists, privacy controls, and so on.

The transition from “On-Board” to “Established,” and the recognition of the “Mitosis” phase are the two areas where most organizations struggle. The first comes from the inability to relinquish some control to the community; the second comes from an inability to recognize the natural evolution of the community as it grows. Mitosis within the community is very healthy. In fact, a healthy community is the cooperative coordination of many smaller communities acting as a whole.

Understanding the life cycle is key to building a comprehensive community strategy, specifically when it comes to moderation and management. A few of the components impacted include: Content creation, group formation, engagement tactics, expert discovery efforts, knowledge sharing practices, and employee participation. Once the strategy is clearly defined, goals and objectives can be identified, clear measurements for success (return on investment) are marked, and the community life cycle becomes the map or playbook for understanding how to reach those goals and objectives.

The three cardinal sins can be avoided if you understand the life cycle of your community, and thus where and how to apply resources and strategy to running it.

Source :mashable.com