The helpful team at Gizmodo have just given us an in-depth look at what they are calling the future of Microsoft: The XBox 360 Kinect and the era of natural user interfaces. Check out this cool post.

Kinect is as much a product of serendipity as anything else. When Microsoft hired Dr. Ilan Spillinger, VP of hardware and technology for Microsoft’s Interactive Entertainment Business, it was to be “deeply engaged on the next-generation Xbox.” Microsoft was looking to go beyond the Wii for its next big project, and about two and a half years ago, it started looking at natural user interfaces. At the same time, it had started looking at 3D cameras and input systems. Virtually in parallel, all of the necessary technology pieces to make Kinect fell into place—in particular, PrimeSense’s 3D sensor.

What Microsoft considers revolutionary about Kinect—and they do consider it revolutionary—isn’t that it tracks your body with full depth mapping, or responds to voice commands, or that it has a standard video camera: It’s that it brings all of three of those things together for the first time. It’s natural user interface in its infancy.

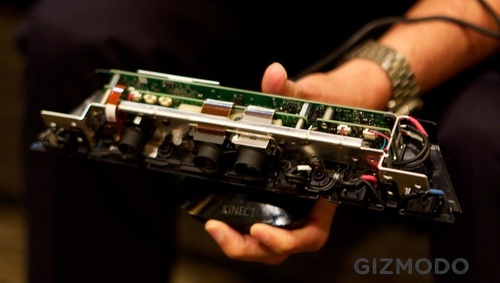

Raghu Murthi, the general manager for Natural User Interface Hardware, is holding a Kinect, stripped naked, as a dozen people gawk at its innards. The exposed metal seems cold. He’s telling us about the optical system—how it sees with the three holes in its head that seem like eyes. Without the plastic housing they look like they’re bulging out. We’re at the beginning of day-long tour of Kinect, gathered in the Great Room, the living room you wish had, but tucked behind a sliding wall inside one of the many food courts on Microsoft’s sprawling campus. 3D sensing has been around for 15 years, Raghu explains. What Microsoft has done, he says, is taken 3D depth-mapping technology that typically costs $10,000 to $150,000, and made it at volume, for cheap.

Raghu Murthi, the general manager for Natural User Interface Hardware, is holding a Kinect, stripped naked, as a dozen people gawk at its innards. The exposed metal seems cold. He’s telling us about the optical system—how it sees with the three holes in its head that seem like eyes. Without the plastic housing they look like they’re bulging out. We’re at the beginning of day-long tour of Kinect, gathered in the Great Room, the living room you wish had, but tucked behind a sliding wall inside one of the many food courts on Microsoft’s sprawling campus. 3D sensing has been around for 15 years, Raghu explains. What Microsoft has done, he says, is taken 3D depth-mapping technology that typically costs $10,000 to $150,000, and made it at volume, for cheap.

The way the optical system works, on a hardware level, is fairly basic. A class 1 laser is projected into the room. The sensor is able to detects what’s going on based on what’s reflected back at it. Together, the projector and sensor create a depth map. The regular old video camera is held at a specific distance away from the 3D part of the optical system in a precise alignment, so that Kinect can blend together the depth map and RGB picture for dynamic, on-the-fly greenscreening.

The Kinect’s size and shape is dictated almost entirely by the 4 microphones located along the bottom. It has to be precisely that large to accommodate the mics and the exact positions they need to be in. The mics, and their placement, is the result of research in 200 homes in the US, Japan and Europe. When you buy a Kinect, one of the first things you’ll do is calibrate the audio to fit the room it’s in. It’s creating an audio profile of the room, mapping out the room’s reflectivity. And if you majorly re-arrange your furniture, you’ll have to do it again.

Basic voice recognition seems like an easy feat—phones do it everyday. But for Kinect, the situation is different. It’s attempting to recognize voices from far away with an open mic without the luxury of push-to-talk telling it when to listen for voice cues. The trick used by Kinect is beam forming, so it can focus on specific points in the room to listen. At the same time, the audio processor is using the echo profile of the room to perform multichannel echo cancellation, so the noise coming out of the TV doesn’t mess with your voice commands. That said, there’s no way to lock out errant voice commands from your douchier friends: it’ll listen to any human being in the room. Even if they have a thick Southern accent, like Hee-haw dipped in red eye gravy, there’s a good chance Kinect will understand them: The acoustical model for every country includes regional accents, so whether you’re from Boston or Alabama, you’ll sound intelligible to Kinect, even if you don’t to the rest of the world.

A row of Kinects line the wall, 16 robot heads nodding silently, endlessly. The motion is robotically smooth, completely un-biological, but alive and almost sentient. We’re inside a Microsoft lab where Kinect is undergoing endurance testing. Xboxes litter the room, their cables hanging out like entrails.

More Kinects are locked in a blue box, a sign warning passersby in all caps, DO NOT OPEN CRITICAL TEST IN PROGRESS. It’s a heat test. Kinect has a tiny built-in fan that kicks in on demand in hot environments, when the heat produced by the three sensors and the atmosphere around it mix to create conditions warmer than Microsoft would like. Joel asks Dr. Ilan Spillinger, VP of hardware and technology for Microsoft’s Interactive Entertainment Business, if the fan isn’t a just bit of over-engineering, a super-insurance policy against heat after the RRoD plague. He replies, “It would good to take it out in the future, and we’ll look into it when we start to integrate the silicon, but right now, even if it’s a small distribution…” in hot environments, they have to have it in there.

The red ring has been seared into the institutional memory of Xbox, undoubtedly. The way Ilan bristles ever so slightly as he tells Joel and I that Trinity, the fresh Xbox, is “a new device, there’s nothing from the past,” make that clear.

I’m more focused on the two Kinect prototypes we aren’t allowed to photograph, one that looks like the head of EVA from Wall-E, a palm-sized bean shape with two antennae shooting out of the side. It was probably rejected for being too personable. The second looks a lot like the current Kinect, but more Apple-like, a glossy black center wrapped in a kind of brushed aluminum.

The final design is chosen because of the mics, as explained earlier, but the shape, the angles are set that way because they’re supposed to angle from the player to the experience. It’s glossy because Microsoft thinks glossy means premium. (Hey guys, guess what? The cheaper matte 360 looks better than the shiny one.)

“Hardware is magic, software is two times magic.”

If any phrase stuck in my head that day, it was Ilan’s utterance about the other half of Kinect, the software. Alone, all of the hardware in Kinect, all the things it’s capable of, wouldn’t amount to much. It’s the software that manipulates the raw data and makes Kinect work.

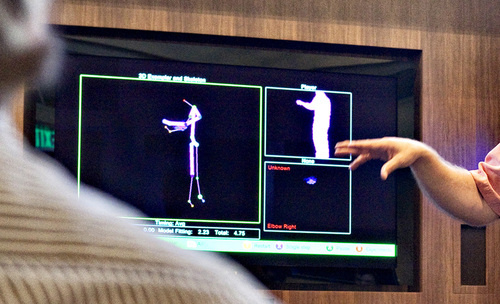

What you look like to Kinect is a vague anthropomorphic shape composed of thousands of undulating, rippling pixels, almost like an ’80s rotoscope effect. The camera pans to the side of the depth map, so we can see a profile shot of what Kinect sees. It’s like something out of Lawnmower Man. Using a built-in database of 20 million images with 200 distinct poses, Kinect converts that raw data, generating a skeleton and reasonable guesses about where all of your body parts are, even if it’s not entirely sure based on visual cues alone—shoulders and long hair are tricky, for instance. That skeleton is what it makes available to the game.

“Theoretically you can have as many people as you want,” Ben Kilgore, Xbox’s general manager, says as Kinect maps the lot of us onscreen, shading us in different primary colors depending on how far back we’re standing. When I line up with another dude, we turn the same color. The “design focus” was for two people though, he adds.

Kinect can identify you via facial recognition using the RGB camera, but it has a second, quick and dirty method, like for turn-based games, using the shape of your skeleton. When I jump up to try it out, it asks me to draw a few circles in the air—a few seconds later it’s calculated who I am, well enough to distinguish from the other guys in the room, anyway.

It would be funny to at least a handful of people that Raghu and Ilan are explaining to me the future of Microsoft and natural user interfaces while we’re seated at a table that is in fact a Surface, Microsoft’s stillborn foray into multitouch interfaces. I like them too much to bring it up. They’re the kind of people you’ve always hope worked at Microsoft: intelligent, strikingly earnest and genuinely interesting. I just hope there are more people like them in Redmond.

Earlier in the day, Ilan insisted to Joel and I that Microsoft is committed to Kinect in a serious way, that it won’t succumb to our big fear, being abandoned like Kin or left to die like Zune, even if the market—you know, people—is slow to react at first. The three pillars of Xbox are, as Raghu sees it: content, Xbox Live and natural UI—Kinect. That’s a bold statement as any about Microsoft’s commitment to Kinect. (Consider, on the other hand, Steve Jobs’ remark that Apple TV is a mere “hobby.”)

Even at the level of Microsoft, it’s hard to see Kinect as anything but hopeful. It’s project that seems to go against the tide of stories about in-fighting between Microsoft divisions, an example of what happens when they actually work together. For instance, its highly developed voice recognition leveraged the work of Microsoft’s speech scientists, and what they learn from Kinect will be fed back into those speech projects. God knows, Kinect isn’t the only Microsoft project that could use a little love from elsewhere in the monolith.

Kinect, Raghu tells me as we’re waiting for a bus to take us to Microsoft’s own anechoic chamber, is Microsoft’s natural user interface platform, the way that Zune is its entertainment platform. In other words, “as it spreads across other platforms” it’ll get better and evolve. The question, the one that engenders possibilities, is which “platforms” it’ll spread across next. Windows with a natural user interface? A Microsoft Word you can truly control with your voice? The idea of computers invisibly embedded throughout your house makes a lot more sense when they’re effortless to control.

It’s not for lack of dreaming. The words “Star Trek” and “holodeck” slip out of Raghu’s mouth effortlessly (which you can hear in the longish interview above). “We think we will be able to replicate holodeck type environments as we go forward. That’s far away from now, but that’s our dream.”

The down-to-earth questions like, “What happens if Kinect completely bombs in the marketplace?” “What if the killer apps don’t arrive?” “What if people just don’t like it?” ‘What about the lag?” “What if it doesn’t work as well as it’s supposed to?” seem almost prudish to consider, at least as long Kinect is still a mostly just a promise, months before it hits shelves. We’d almost rather dream while we can.

Source: Gizmodo.