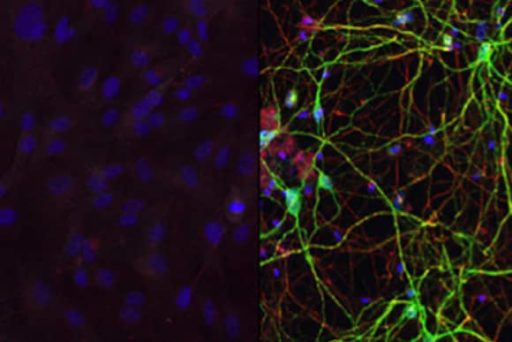

Researchers at Duke University, funded by Darpa, have developed a biosensor that has the ability to know if you’re sick with a virus infection even before your first sneeze. The sensor detects changes in gene expression that occur in people exposed to viruses like the common cold, flu, or the respiratory syncytial virus. This approach would allow physicians and public-health officials to make quick diagnoses before someone even appears sick. Current tests look for presence of the actual pathogen, but that takes longer and doesn’t work until a person has symptoms.

Led by Dr. Geoffrey Ginsburg, director of Duke’s Institute for Genome Science & Policy, the team identified 30 genetic markers that are activated by viruses. In some cases, the changes occurred hours or days before symptoms started.

The team started human trials last year, monitoring 80 people in four studies. Healthy people were exposed to three viral strains, and their blood, urine and saliva were then tested for specific gene signatures that would characterize illness, DangerRoom reports.

The next step is to analyze an ongoing study of Duke freshmen living in dorms. Participants were asked to file daily reports about their health and provide blood and other samples as requested, according to a university news release.

Darpa provided $19.5 million to fund the study, seeing potential in a system that can evaluate military personnel before they’re deployed. An early-warning system could also help quarantine troops before they can infect others.

The research could lead to public-health benefits well beyond the military, however. The team also found that genetic signatures for viral infections are different from those triggered by bacterial infections. Definitive information about a patient’s ailment can make antibiotic-resistant superbugs less likely, if fewer doctors prescribe antibiotics when they’re not necessary.

What’s more, public health agencies could use the technology to isolate outbreaks of influenza virus, possibly stemming pandemics before they can spread.

Source: Popular Science.