Engineers at the University of Utah are working to build a wireless network to noninvasively measure the breathing of surgery patients, adults with sleep apnea, and babies at risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), iIn order to accomplish this, Patwari surrounded himself with 20 wireless transceivers operating at a frequency of 2.4GHz. He timed his breathing to be about 15 breaths per minute, confirming this measurement with a carbon dioxide detector and the algorithm accurately measures respiration within 0.4 to 0.2 breaths per minute based on only 30 seconds of data, much better than most monitors, which round off to the nearest full breath. The system will also be cheaper than existing breath monitors and it uses off-the-shelf wireless transceivers similar to the ones used for home computer networks……………..

University of Utah engineers who built wireless networks that see through walls now are aiming the technology at a new goal: noninvasively measuring the breathing of surgery patients, adults with sleep apnea and babies at risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Because the technique uses off-the-shelf wireless transceivers similar to those used in home computer networks, “the cost of this system will be cheaper than existing methods of monitoring breathing,” says Neal Patwari, senior author of a study of the new method and an assistant professor of electrical engineering. While he estimates it will be five years until such a product is on the market, Patwari says a network of wireless transceivers around a bed can measure breathing rates and alert someone if breathing stops without any tubes or wires connected to the patient. “We can use this to increase the safety of people who are under sedation after surgery by knowing if they stop breathing,” he says. “We also envision a product that parents put around their baby’s crib to alert them if the baby stops breathing. It might be useful for babies at risk of SIDS.” The American Academy of Pediatrics says there is “no evidence that home monitors are effective” for preventing SIDS. Since 2005, the group has opposed the use of breathing monitors to prevent SIDS, but has said they “may be useful in some infants who have had an apparent life-threatening event,” including some combination of apnea [abnormal interruptions in breathing], color change, limpness and choking or gagging. “The AAP recognizes that monitors may be helpful to allow rapid recognition of apnea, airway obstruction, respiratory failure, interruption of supplemental oxygen supply, or failure of mechanical respiratory support,” the group states.

In addition to other possible uses, Patwari wants to conduct research with doctors to test his method as an infant-breathing monitor and, if it proves useful, develop it as a medical device that would need federal approval. He also says it may be useful for adults with sleep apnea, which causes daytime fatigue and impairs a person’s performance. SIDS monitors now on the market include FDA-approved medical devices that measure heart rate and respiration and are connected to babies with wires, electrodes and-or belts. Other monitors, which are non-medical and over-the-counter versions, detect a lack of sound, or use mattress sensors to detect a lack of movement. Patwari says that with the new method, “the patient or the baby doesn’t have to be connected to tubes or wired to other sensors, so they can be more comfortable while sleeping. If you’re wired up, you’re going to have more trouble sleeping, which is going to make your recovery in the hospital worse.” Some opposition to SIDS monitors is based on a fear that parents will depend on monitors instead of following other, more effective medical measures, including always placing babies on their backs to sleep, keeping redundant bedding and soft objects out of the crib, and not having babies share a bed with adults. Yet many parents want monitors too. The AAP acknowledges “distribution of home monitors continues to be a substantial industry in the United States.” Because of efforts to patent the new use of the wireless breathing-detection technology – which has been named BreathTaking – Patwari is posting his study on the online scientific preprint website ArXiv this week before submitting it to a journal for formal publication.Patwari conducted the study with Wilson; Sai Ananthanarayanan, a postdoctoral electrical engineer; Sneha Kasera, an associate professor of computer science; and Dwayne Westenskow, a professor of anesthesiology and research professor of bioengineering. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

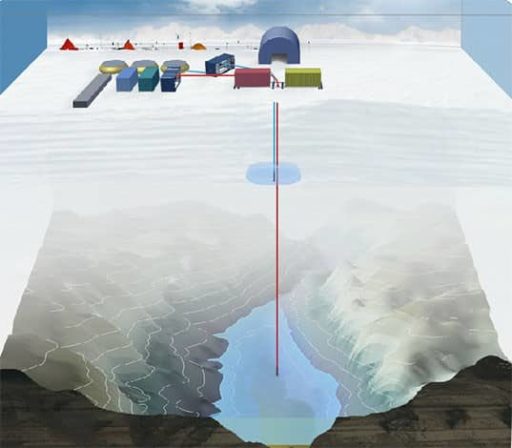

In a new study, Patwari showed a network of 20 wireless transceivers placed around a hospital bed could reliably detect breathing and estimate breathing rate to within two-fifths of a breath per minute based on 30 seconds of data. This is different than using wireless transmitters to relay measurements from conventional breathing monitors. The motion of the chest and abdomen during breathing impedes the wireless radio signals crisscrossing a bedridden patient, who in the study was Patwari himself. Each of the 20 transceivers or nodes can transmit and receive to the other 19, meaning there can be up to 380 measurements (20 times 19) of radio signal strength within a short period of time (the transceivers transmit one after the other). The study was conducted in a clinical room used for research at the University of Utah School of Medicine’s Department of Anesthesiology. Patwari reclined on a hospital bed and listened to a metronome to time his breathing so he inhaled and exhaled 15 times per minute – about the average breathing rate for a resting adult. His breathing was measured two ways: by the experimental wireless network, and by a carbon dioxide monitor connected to his nostrils by tubes. It calculated breathing rate by measuring the amount of carbon dioxide exhaled with each breath. Patwari also tested the wireless network with no one in the hospital bed.

The study found the wireless network could measure breathing within 0.4 to 0.2 breaths per minute, an insignificant error rate given that most breathing monitors round to the nearest breath per minute, he says. If a bedridden person or baby moves, the wireless system detects the movement but cannot measure their breathing at the same time. To decide if someone is breathing or not, the wireless system uses a computer algorithm – basically, a set of formulas. Patwari says his algorithm squares the amplitude or loudness of the signal on each link between nodes, then averages it over all 380 links. A number larger than 1.5 indicates breathing has been detected. Patwari also measured how many nodes were required to measure breathing accurately. The minimum was 13 nodes or transceivers, while the rate of incorrect breathing measurements fell to zero when 19 nodes were used. The study also showed the height of the nodes around the hospital bed didn’t significantly affect breathing measurements. Patwari plans more research on whether different or multiple radio frequencies might detect breathing better than the one 2.4 gigahertz frequency used in the study. He also wants to test whether the system can detect two people breathing at the same rate but not in sync – something that might make it possible to design a system that could detect not only the location of hostages in a building, but the number held together.

[ttjad keyword=”general”]