Until now, researchers had assumed that 80% of our DNA is functional. But lately, researchers at the University of Oxford have found that a mere 8.2% of the human DNA is functional!

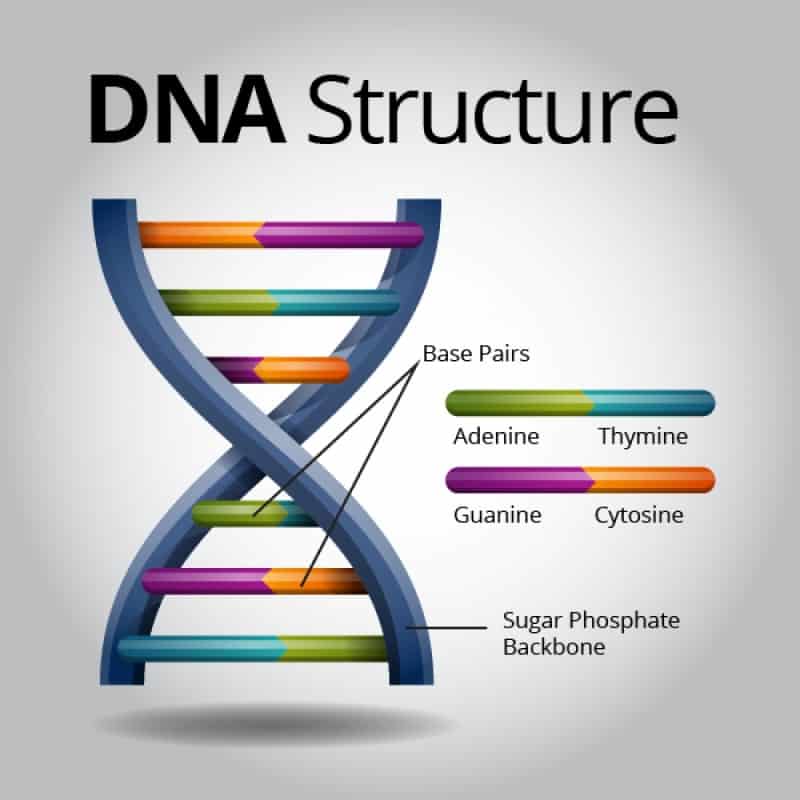

Our DNA is made up of 3.2 billion base pairs- the chemical building blocks found in chromosomes that are strung together to form our genome. It’s a pretty impressive number, but how much of this DNA is functional? That has been a subject of great interest recently given revelations about the vast amount of “junk” DNA, or DNA that does not encode proteins, that seems to be present. In fact, almost 99% of the human genome does not encode proteins.

Back in 2012, scientists from the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project claimed that 80% of our DNA has some biochemical function. However, many scientists were not satisfied with this assertion given that the word “function” is hazy and too broad. In particular, DNA activity does not necessarily have a functional consequence. Researchers therefore needed to demonstrate that the activity is important.

To do this, Oxford researchers looked at which parts of our genome have avoided accumulating mutations over the last 130 million years. This is because slow rates of genomic evolution are an indication that a sequence is important, i.e. it has a certain function that needs to be retained. In particular, they were looking for insertions or deletions of DNA sequences within various different mammalian species, from humans and horses to guinea pigs and dogs. While this can occur randomly throughout the sequence, the researchers would not expect this to happen to such an extent in stretches that natural selection is acting to preserve.

Now the researchers have found that 8.2% of our DNA is presently functional; the rest is leftover material that has been subjected to large losses or gains over time.

Gerton Lunter, lead researcher of this new study from the University of Oxford’s Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics in the UK, said, “We found that 8.2 percent of our human genome is functional. We cannot tell where every bit of the 8.2 percent of functional DNA is in our genomes, but our approach is largely free from assumptions or hypotheses. For example, it is not dependent on what we know about the genome or what particular experiments are used to identify biological function.”

On the other hand, researchers have also noted that not all of this 8.2% is equally important. As mentioned, only 1% of our DNA encodes the proteins that make up our bodies and play critical roles in biological processes. Researchers believe that the remaining 7% plays regulatory roles, switching genes on and off in response to environmental factors. You might be thinking, what happens to the rest 91.8% DNA? Well, they are called “lazy.”

Lutner said, “The rest of our genome is leftover evolutionary material, parts of the genome that have undergone losses or gains in the DNA code.” On the other hand, lead author Chris Rands said in a news-release, “A little over 1 percent of human DNA accounts for the proteins that carry out almost all of the critical biological processes in the body. The proteins produced are virtually the same in every cell in our body when we are born to when we die. Which of them are switched on, where in the body and at what point in time, needs to be controlled—and it is the 7% that is doing this job.”

Another interesting finding was that while the protein-coding genes were well conserved across the different mammalian species investigated, the regulatory regions experienced a high turnover, with pieces of DNA being added and lost frequently over time. While this dynamic evolution was unexpected, the majority of changes in the genome occurred within the so-called “junk” DNA.

Co-author Chris Ponting said, “We are not so special. Our fundamental biology is very similar. Every mammal has approximately the same amount of functional DNA, and approximately the same distribution of functional DNA that is highly important and less important.”

The study has been published in the journal PLOS Genetics.

Source: University of Oxford

Thanks To: Sci-News, IFL Science

[ttjad keyword=”ultrabook”]